Alongside his scientific research, Mike has advised the government on space weather science and impacts and also provided scientific advice to the writers of Cobra, a new six-part TV drama. He explains the facts behind the fiction.

Please note, this blog contains spoilers!

UK political TV drama “Cobra" was released earlier this year to the great interest of myself and other colleagues involved in the science and impacts of space weather. The trigger for the drama is the disruption caused by severe space weather event and the UK government's reaction to it.

The series takes its name from the acronym for “Cabinet Office Briefing Room", the location where UK government ministers meet with officials to decide how to address major national crises. In the first episode we first see ministers being advised that growing activity on the Sun brings the risk of a severe space weather event. This growing activity leads to a series of COBR meetings where ministers are briefed as space weather events arrive at Earth, leading to disastrous impacts on aviation and electricity supplies.

I very much enjoyed Cobra. I'm sure some folks will get picky about details - seeing the trees rather than the wood. But the series picks up on many of the key points that have emerged from discussions my colleagues and I have been having on space weather impacts over the past decade (see below for further reading). It is an engaging drama that does a good job of addressing the science of space weather and its potential impacts. It really brings home why we need to get on with building the next generation of observational networks to monitor space weather coming from the Sun.

In the TV series the space weather event arrived first in the form of a radiation storm, leading to the crash landing of a disabled aircraft. While radiation might have profound effects on modern electronic systems in aircraft, in practice the UK is actively seeking to ensure this never happens. For example, the ChipIR project is a world-leading facility to test avionics for these effects, led by the STFC's ISIS Neutron and Muon Source. The SWIMMR programme led by RAL Space includes work to improve our ability to model and measure how radiation from space reaches aircraft altitudes (12-20km). The scene brings out why we need these scientific projects and programmes.

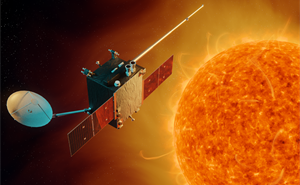

The first episode ends with the lights going out as the electric power grid fails. We know that the major risk to power grids comes from a severe geomagnetic storm driven by the arrival at Earth of a huge, fast coronal mass ejection (CME). Fortunately, most CMEs miss the Earth. At RAL Space, we are now working with partners to develop ESA's Lagrange mission. This will be the next generation of imagers that will give better warnings of Earth-directed CMEs.

The first episode ends with the lights going out as the electric power grid fails. We know that the major risk to power grids comes from a severe geomagnetic storm driven by the arrival at Earth of a huge, fast coronal mass ejection (CME). Fortunately, most CMEs miss the Earth. At RAL Space, we are now working with partners to develop ESA's Lagrange mission. This will be the next generation of imagers that will give better warnings of Earth-directed CMEs.

Another point explained well within the show was that the strength of a geomagnetic storm depends on the orientation of the magnetic field embedded in the CME. A northward field leads to only a modest storm, but a southward field can produce a severe and dangerous storm. The characters noted that northward and southward fields are equally probable, and that currently we can only determine the field when the CME passes over a satellite orbiting the so-called L1 point, 1.5 million kilometres sunward of Earth. There is an excellent scene where COBR participants do the maths, and realise that this gives no more than 30 minutes warning time. This simple maths has been at the heart of many discussions I have been part of on the space weather risk that the UK faces.

The primary impact of space weather on a power grid is to cause voltage instability. Safety systems will then shutdown part or all of the system leading to a short period of blackout whilst the storm passes and the grid is brought back on-line (as briefly happened in parts of Scotland during a geomagnetic storm in July 1982). This is the focus of the second episode as people try to make the best of a night without power – in some cases with dramatic consequences. It's a reminder that we all need the ability to cope with short power cuts - and to do so safely!

There is also a small risk that space weather can damage the huge transformers that raise and lower voltages as electricity flows across the National Grid from power stations to local distribution networks. Transformer damage is rare but can happen (two UK transformers suffered minor damage during the great geomagnetic storm of March 1989) and, of course, could make it more difficult to get the lights back on.

There is also a small risk that space weather can damage the huge transformers that raise and lower voltages as electricity flows across the National Grid from power stations to local distribution networks. Transformer damage is rare but can happen (two UK transformers suffered minor damage during the great geomagnetic storm of March 1989) and, of course, could make it more difficult to get the lights back on.

In the TV series this is played dramatically with damage to four transformers causing extended blackouts in the areas served by those transformers. This is dramatic licence, but drives the subsequent drama in which there are many struggles to bring in a replacement transformer (size of a small house) into the worst-affected region. In practice, the UK power grid is resilient to the loss of a single transformer at any grid substation – all substations have at least two transformers, a design decision made more than half a century ago. So it's very unlikely the UK would experience such long blackouts as shown in the series. But we can and should reflect on the need to keep that resilience.

Cobra gives a great outline of how a severe space weather event might play out. It is an extreme interpretation, but that's necessary to make strong drama. Fortunately, the UK has done a huge amount of work since 2010 to make sure that this extreme interpretation does not happen here. A national forecast centre has been set up at the Met Office, we've developed awareness across government and key industries, there has been investment in scientific research, and now in the research-to-operations work that is vital to convert science into useful services.

From a scientific point of view, there are two key messages we can draw from Cobra. The obvious one is that the work done to protect against severe space weather needs to be sustained – and sustained forever, as with measures against other natural hazards like flooding and pandemic flu. Like those hazards we can expect very bad conditions to occur maybe once or twice a century, but it is still a risk that must be addressed.

The more subtle message is back to the scientific community. When you watch the series you will see that our job is to scientifically support political and official decision-makers. To do that we need to understand their needs, how scientific advice has to be melded with a host of other issues, some relevant to the technical work, many by the need to reassure people, and some thrown up by politics. As is clear in the UK ethical code for scientists, we have not only to be honest and accurate in what we say, but we must also listen to the concerns of others outside the scientific community. The series shows this well – that tough decisions are the responsibility of political leaders, so we must present our science in ways that can help them.

Please note: Cobra has an 15+ age rating.

Images:

Top: Artist's impression of ESA's Lagrange mission. Credit: ESA/A. Baker, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

Middle: National Grid transformer on route to installation. Credit: National Grid https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/

Bottom: Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) on the Sun from 22 July 2012 until 23rd July 2012 missed the Earth by some 120 degrees in solar longitude. As as observed by many instruments including the RAL Space led Heliospheric Imagers on NASA's STEREO satellites. Credit: NASA/STEREO

Further Reading:

Extreme space weather: impacts on engineered systems and infrastructure, 2013 report of Royal Academy of Engineering)

Oughton, E.J., Hapgood, M., Richardson, G.S., Beggan, C.D., Thomson, A.W.P., Gibbs, M., Burnett, C., Gaunt, C.T., Trichas, M., Dada, R. and Horne, R.B. (2019), A Risk Assessment Framework for the Socioeconomic Impacts of Electricity Transmission Infrastructure Failure Due to Space Weather: An Application to the United Kingdom. Risk Analysis, 39: 1022-1043. doi:10.1111/risa.13229

https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13229

Eastwood, J. P., Hapgood, M. A., Biffis, E., Benedetti, D., Bisi, M. M., Green, L., et al. ( 2018). Quantifying the economic value of space weather forecasting for power grids: An exploratory study. Space Weather, 16, 2052– 2067. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018SW002003

Hapgood, M. (2017). Space Weather, ISBN: 978-0-7503-1372-8. Bristol, UK: IOP Publishing, 2017. Free download on https://iopscience.iop.org/book/978-0-7503-1372-8 in Kindle, PDF and ePub formats.